Brett Johnson, one of the world's best cyber thieves before he became one of the good guys, reads the headlines and know he's missing out on easy pickings. The pandemic put healthcare facilities on the map for cybercriminals, and news reports about providers paying astronomical sums to get back confidential patient information or unlock computer systems crucial to caring for patients are routine. The successful extortion schemes have reaped cyber thieves multimillion dollar ransoms and have cost healthcare systems billions of dollars.

Healthcare cyberattacks are going to increase and intensify, according to Mr. Johnson, whom the Secret Service nicknamed "The Original Internet Godfather." For a brief moment after the pandemic hit, the 51-year-old Mr. Johnson was tempted to come out of retirement.

"I'm the only fraudster on the planet who didn't get rich last year," says Mr. Johnson, who now consults for corporations to help prevent them from being victimized by the cybercriminals with whom he once conspired. "Everyone else did. It was such easy money."

Mr. Johnson's former life of crime began in Kentucky when he was 10 years old. His mother — a drug addict, alcoholic and con artist herself — left him and his sister alone with nothing to eat for days at a time. He learned how to steal food out of necessity and expanded his stealing over the years. Eventually, he created ShadowCrew, an online message board for cybercriminals that was a precursor to similar networking sites now prevalent on the dark web.

Mr. Johnson was on the FBI's list of most wanted cybercrooks when he was arrested in 2006 and charged with 39 felonies. He served seven years in prison and eventually became an FBI informant and consultant with the feds. He's been on the straight and narrow — "legal," as he puts it — for nearly six years.

Had he wanted to, Mr. Johnson could have been involved in the recent rash of cyberattacks on healthcare providers. A report from Comparitech, which reviews and compares cybersecurity products, says there were 92 ransomware attacks on healthcare facilities in the U.S. in 2020 — a 60% increase from 2019 – that affected more than 600 clinics, hospitals and organizations. The attacks involved more than 18 million patient records and cost facilities nearly $21 billion, most of which was from downtime due to crippled computer systems.

In October 2020, the FBI, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency warned that healthcare facilities were being targeted by Ryuk and Conti ransomware gangs and TrickBot and Bazaloader malware for financial gain, and called the attacks an imminent threat.

Three months later, the IT vendor of Harvard Eye Associates and Alicia Surgery Center, both in Laguna Hills, Calif., paid hackers an undisclosed amount to regain the stolen data of nearly 30,000 patients. Scripps Health, a $3.1 billion nonprofit healthcare provider in San Diego, was victimized by a ransomware attack in May. Scripps took down its computer systems, which resulted in restricted access to patients' electronic medical records and disrupted operations at its hospitals and facilities. The cyber thieves made off with the personal information of nearly 150,000 patients. "We deeply regret the concern this incident has caused for our patients, employees and physicians," Scripps CEO Chris Van Gorder wrote in a recent San Diego Union op-ed. "There are important lessons to be learned — Scripps, like other healthcare systems, is taking further steps to enhance our information security, systems and monitoring capabilities, and adapt to this evolving cyber-threat landscape."

Cybersecurity threats go beyond health care. Facebook and CVS have had recent data breaches. In May, a Russian cybercrime group shut down the U.S. facilities of JBS, the world's largest meat processing company. The same month, Colonial Pipeline was shut down by a ransomware attack and reopened after the company paid the thieves $5 million. Before last year's elections, the U.S. Cyber Command conducted offensive operations to prevent interference by groups in nine countries, including Iran and Russia.

Mr. Van Gorder believes government help is needed to combat the issue. "Just as protecting the public's health during a once-in-a-century pandemic takes a village, so will protecting our hospital systems, critical infrastructure, schools, businesses and government entities from criminals who exist in the shadows," he wrote.

The traditional trajectory for cybercriminals is to start with credit card theft, according to Mr. Johnson. He says the pandemic led legions of these threat actors to engage in fraudulent schemes for unemployment and stimulus checks for the first time. The crimes were easy to commit and left many cyber thieves flush with money, which in turn gave them the time to innovate and brainstorm about what industries haven't been hit on a regular basis.

"Many determined that the medical community was wide open for attacks," says Mr. Johnson. "Anyone who thinks healthcare ransom attacks have peaked is completely wrong."

When Mr. Johnson was running ShadowCrew, cybercriminals often showed up with stolen patient data that they couldn't give away. Now, the thieves are seeing that it could have value and Mr. Johnson believes mass attacks are inevitable.

"Cybercriminals see healthcare systems as easy targets, because they're almost forced to pay the ransoms," he says. "Not doing so could be a matter of life and death for patients."

Many healthcare systems practice good cyber hygiene by investing in strong firewalls, regularly updated anti-malware software and ongoing employee training. Still, gaps in cybersecurity remain, partly because healthcare workers who are rightfully focused on providing patient care undervalue the importance of maintaining a noncorrupted computer network. Convincing them to emphasize cybersecurity is an important challenge for healthcare leaders.

"Outpatient facilities have to be as concerned about protecting their data as they are about the physical welfare of their patients," says Mr. Johnson. "The entire industry doesn't understand the magnitude of the dangers associated with data compromise."

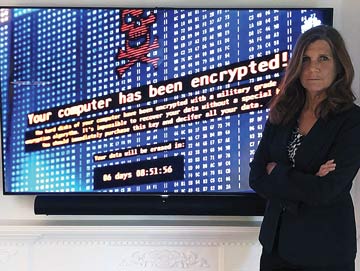

Kathy Hughes monitors Northwell Health's cybersecurity dashboard and knows some threats are going to slip through the security technology in place at New York State's largest healthcare provider.

Emails sent to Northwell's 70,000 employees at 23 hospitals and more than 830 outpatient facilities remain the biggest concern for Ms. Hughes, the company's chief information security officer. But the threat is spreading to medical devices and other automated systems that provide hidden doors through which cybercriminals can access the health system's financial records and confidential patient information. COVID-19 amplified that threat.

"The healthcare industry has been heavily targeted for several years, but it got much worse when COVID-19 hit and threat actors realized the pandemic made us much more vulnerable," says Ms. Hughes. Cyber thieves know that the deep desire healthcare workers have to help patients brings with it a built-in level of naivete that makes it hard for them to sniff out a con artist, especially when emails arrived during an unprecedented health crisis about the availability of personal protective equipment, vaccines and cures. "Staff members were desperate and looking for solutions, and they were responding to these types of messages," says Ms. Hughes.

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)