- Home

- Article

Throw Away the Script

By: Scott Sigman

Published: 2/12/2019

Share:

With opioid-sparing surgery, most patients won't need prescription painkillers.

Becoming an opioid-sparing surgeon was the most liberating thing I've done in 25 years of practice. Why? Because before I started down this revolutionary path, I'd unwittingly become a pain-management specialist. True, I was an orthopedic surgeon and a healer — what I wanted to be — but I was also writing prescriptions for narcotics. And I was writing refills. And I was spending time trying to wean patients off their medications, because 20% were popping them like Jujubes — very early on showing signs of dependence, abuse and addiction. Plus, I was getting calls at all hours of the day and night, and had to be concerned about patients calling me on weekends.

Not anymore. Now, 5 years later, I'm still a healer of knees and shoulders, left and right, but that's it. Not because I don't care about my patients. I care deeply about them. But because, thankfully, we've figured out how to manage and minimize pain, so that they — and I — no longer have to worry about whether opioids might ruin their lives.

It's important to remember just how this profound and deadly opioid crisis came about — how it is that 4 out of 5 heroin users started with prescriptive opioid medications.

It happened because we succumbed to misinformation and an absurd proposition. The misinformation we were fed was that opioids are inexpensive and non-addictive. Both of those assertions turn out to be patently false. The absurd proposition was that we could and should consider pain a vital sign, and that we had to make sure our patients were completely pain-free. We were told, in fact, we would be graded on our work. Pain would be quantified on a 1 to 10 scale, and if our patients weren't zeros or ones, our hospitals could be penalized and our satisfaction ratings would surely plummet.

And yet we all knew that the notion that pain is objective and measurable is ridiculous. We can objectively measure blood pressure, pulse rate and oxygen saturation. But pain is subjective. One patient's 3 is another patient's 5, or 7 or "worst pain of my life."

And as for opioids being cheap and safe, little could be further from the truth. They're highly addictive. Twenty percent of patients who complete a 10-day course of opioids begin to show signs of addiction. And though they may be cheap up front, once you consider the loss of life, the economic impact of substance-abuse disorder and the cost of managing addiction, they're tremendously expensive to society — much more expensive than the alternatives.

Fortunately, times are changing. I used to feel like a lonely voice in this battle. Now, there's a large cadre of opioid-sparing surgeons who are more than willing to have this essential conversation. And every day, more surgeons are converting.

An awakening

MINIMIZE As opioid addiction has reached crisis proportions, Dr. Sigman says surgeons in a variety of fields have worked to reduce the need for opioids after procedures, in the hope that fewer patients would become dependent on or addicted to pain pills.

| Caitlin Mahoney, NP-C

Now for the slightly controversial part of my story. In addition to becoming aware of breakthroughs in multimodal pain regimens — combinations of non-opioid medications that target specific pain pathways — the turning point for me came when my partner, David Prybyla, MD, told me about a journal article he'd read on liposomal bupivacaine. (He reads a lot more than I do.)

I know what you're thinking. And it's true. Liposomal bupivacaine (Exparel) has become the licorice — or maybe Grateful Dead — of the medical world. You either love it or you hate it. I'm keenly aware that of the thousand or so journal articles that have been written about it, roughly 500 are pro and 500 are con.

Here's my view: I think of it as more a medical device than a pharmacologic process. In other words, you have to use it the right way or you won't get the results and outcomes you want.

What's the wrong way? The first mistake surgeons make with Exparel is not using enough. You have to infuse the entire surgical area, or the liposomes won't reach all the nerves that have been injured. The second mistake they make is not putting it in all the right places. For example, with total knee replacements, you absolutely have to inject the posterior capsule. In many of the "con" papers I've seen, the researchers failed to do that. If you inject it everywhere else but miss the posterior capsule, you might as well not bother, because the posterior capsule is really going to hurt.

The point is, there are about 5 million liposomes in a 20-cc vial, but they don't know where to go; they only know what to do. They'll only work if you put them into all the right places. You have to mix the medication to a volume that lets you get to where you need to go.

Admittedly, the company that markets liposomal bupivacaine (Pacira Pharmaceuticals) is partly to blame for some of the early failures. They were a new company with one product, and, in retrospect, they could have done a better job of conveying a clear message and clear instructions.

Ultimately, Dr. Prybyla and I used trial and error to figure out the where and the how much. For a total knee, is 40 cc's enough? How about 60 cc's? It turns out that 120 cc's is the right volume for a total knee. We use 20 cc's of Exparel, 20 cc's of Marcaine 0.25%, and 80 cc's of saline. Again, you have to make sure the liposomes reach every area and nerve that has been injured.

These days, when I'm giving talks about opioid-sparing techniques, I know at least one person in the audience is going to come up afterward clutching an article that says liposomal bupivacaine doesn't work — and that's why they don't use it. I say, great, let's read the article together, really get into the nuts and bolts of it, and I guarantee I'll be able to show you exactly why it didn't work the way it was supposed to.

The protocol

PRECISION PLACEMENT You have to use Exparel (liposomal bupivacaine) the right way or you won't get the results and outcomes you want.

| Scott A. Sigman, MD

Of course, as I mentioned, there's more to opioid-sparing surgery than just liposomal bupivacaine. Pre-operatively, we work with anesthesia providers and administer a multimodal cocktail that includes a standard dose of IV Tylenol (Ofirmev) and 200 mg of Celebrex.

Post-operatively, I write a prescription for Tylenol 1000 mg po q8. Writing the prescription is important, because we don't want patients to think it's just an elective. We also use the NSAID Meloxicam 15 mg po qd, because it doesn't require pre-authorization, and Gabapentin 300 mg po qhs, which is to be taken only at night. The reason: It helps with sleep, and it manages pain in a different pathway. Patients take each medication for 5 days.

Clear understanding of the protocol is essential, of course, so we go over it post-operatively with patients so many times that by the time they're ready to leave, they can tell the next patient what the protocol is. And of course, if needed, we use interpreters or explain everything to family members. Finally, we call patients the day after they get home and review the protocol one last time.

The 3-day storm of pain

The key to all of this is getting patients through what I call the storm of pain — the first 3 days after surgery. If you're simply giving patients a nerve block and sending them home, that block is going to wear off in 12 to 18 hours. They may be all smiles when they leave your facility, but then at the worst possible time, like 2 or 3 in the morning, the block is going to wear off and they're going to be miserable.

So, they'll start crunching down on the pain medication. But once they're behind, they can't get ahead of the pain. Once it starts, there's something about that kind of pain that makes it hard to keep up with. Then what do they do? What they might do is end up taking opioids for the next 6 weeks.

We're providing a soft landing for them, instead. We've done this with hundreds of patients and they typically have a motor block for 24 hours, a sensory block for 36 hours and an analgesic effect that lasts anywhere from 2 to 3 days. They're getting pain relief throughout that 72-hour window — the storm of pain. After that, the pain is usually much more tolerable and manageable.

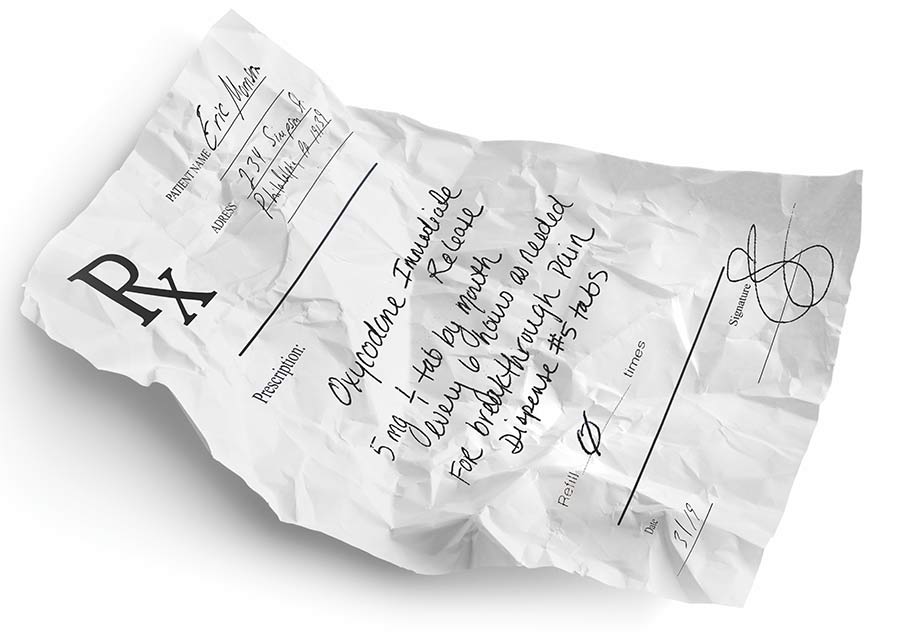

Incidentally, just in case, we also prescribe 5 doses of a short-acting, immediate-release opioid — immediate-release oxycodone, not extended-release OxyContin — and we encourage patients not to take it. In fact, we tell them they don't even have to fill the prescription if they prefer not to.

EASY ACCESS Anyone can quickly learn opioid-sparing protocols for rotator cuffs, total shoulders, total knees, total hips and other procedures, says Dr. Sigman, seen here doing a knee arthroplasty for a crowd.

Which brings up another important point: Patients have to understand that it's OK to have some pain after surgery, that they should expect it (see "Pre-op Conversation Sets Tone for Opioid-sparing Surgery"). When I consent patients in my office, I tell them my expectations about pain management, and I tell them I want to hear theirs. I explain that I don't expect them to be pain-free, but I do expect to get them to where they're comfortable.

Almost invariably, they're relieved by that conversation. Because nearly everybody knows somebody — a brother or a friend or a colleague — who's had a problem with opioids. Bottom line: To be a successful opioid-sparing physician, you must have that conversation with your patients.

Cookie-cutter techniques

I recently participated in a surgeon advisory panel charged with developing opioid-sparing surgical interventions. I was on the team that developed ACL protocols. We got 8 of the top ACL surgeons in the country together in one room, along with 3 outstanding anesthesiologists. Then we shut the door for a few days.

We looked at the anatomy of the knee, knowing that the anterior femoral cutaneous nerve has 3 branches that provide pain after surgery, and that there's also the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve. The approach we developed involves localized cutaneous blocks to those cutaneous nerves. We then inject the site in which the graft is taken. Whether it's the quadriceps, the patellar or the hamstring, it's the same concept. You also inject the portals, the site where the graft goes into the tibia, and the site where the graft comes out of the femur. And for ACLs, the block consists of 20 cc's of liposomal bupivacaine, 20 cc's of Marcaine 0.25% and 40 cc's of saline. The pre- and post-operative protocols are the same as those described earlier.

The panel has also developed opioid-sparing protocols for rotator cuff surgery, total shoulders, total knees and total hips, all of which can be done outpatient. We also have opioid-sparing spine protocols, trauma protocols for orthopedics and protocols for specialties outside of orthopedics.

The key to becoming an opioid-sparing surgeon is getting patients through the storm of pain — the first 3 days after surgery.

You can view all 10 "opioid-minimizing approaches" at osmag.net/eU6McE. As you'll see, they're all very specific cookie-cutter techniques, designed that way so there's zero confusion. The videos show exactly where to put each of those 10cc syringes to get the appropriate zone of action. You can watch them and within 24 hours become an opioid-sparing surgeon who'll have good outcomes that are both predictable and reproducible.

CMS on board

An important piece of good news for those who want to help mitigate the opioid crisis is that CMS is now willing to pay for opioid alternatives for Medicare patients in the ambulatory surgery center setting. That helps with one of the major areas of pushback: the cost of Exparel, which is $330 for a 20-cc vial. That can be a budget-buster for many pharmacies, even if surgeons want to practice opioid-sparing surgery. Fortunately, at least one major commercial insurer is moving in the same direction. We hope the new approach will be carried over to the inpatient setting, as well, although CMS hasn't yet said one way or the other.

Fighting the next wave

Finally, I want to make it clear that I'm not against opioids in all situations. Some people with chronic pain can function despite being addicted to opioids. They can hold down a job, drive a car and live their lives. Opioids also have a place in the management of cancer patients. I'm certainly not advocating eliminating them from our society.

What I am advocating is trying to minimize the next wave of patients who have the potential to become part of this crisis. Most patients will tell you the same thing: They started taking opioids and really didn't like the way they felt, so they stopped. But the ones who get addicted will tell you, "I took my first pill and I felt great!" Their bodies and their brains light up, and then we see patients who go through 40 pills in 3 days and are already asking for more.

The problem is there are no identifiable markers — no way to predict who those susceptible patients are. I choose to try to make my patients as opioid- naive as possible. I minimize the exposure upfront, and then we never have to find out. We now have the capability to do that — to control pain without relying on opioids, to throw away the script. OSM

Editor's note: Dr. Sigman has consulting agreements with Pacira Pharmaceuticals and with DePuy Synthes, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson.

MANAGING EXPECTATIONS

Pre-op Conversation Sets Tone for Opioid-sparing Surgery

When it comes to pain, surgeons need to prep their patients well before they head into the OR. If you don't have that conversation, you're not doing your job, says Dana LaVanture, MD, FACS, a board certified hand surgeon in the department of orthopedics at Guthrie Robert Packer Hospital in Sayre, Pa.

"Patients are relying on you and trusting you to do the procedure," says Dr. LaVanture. "They should be able to count on you to help them not just manage that pain, but also to understand that pain."

It's good to let patients know about the degree of pain they should expect. A soft tissue procedure will usually come with significantly less pain than one that deals with bone. Patients have different degrees of pain tolerance, so it's important to ask if they've required pain medicine during previous procedures. The conversation is specific to every patient.

Patients who expect more pain have more pain.

"I live in a rural area, and we have a lot of farmers and laborers who don't have the expectation that they will have no pain," says Dr. LaVanture. "For those people, pain management can be easier." Sometimes, all patients need is a little bit of direction. That pre-op reassurance can help set the tone for patients that they don't need opioids.

"Patients anticipate more pain than they actually have," says Dr. LaVanture. "Patients who expect more pain have more pain." Earlier in his career, Dr. LaVanture commonly prescribed opioids for his post-op patients. Then, he started looking at how few of his patients were actually filling those prescriptions.

"Now I prescribe very few," he says.

The key is always to get the conversation going early.

"You can't be afraid to talk to the patients," he says. "The most important thing is talking to them and having that discussion."

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)