Preoperative collaboration and consensus is crucial to avoid adverse intraoperative events involving obese patients with difficult airways.

When it comes to airway management, ENT procedures present a unique challenge, as both the surgeon and the anesthesia provider are working in the same area. A recent article examined the communication issues between these two providers with the goal of eliminating intraoperative disagreements and danger.

The paper, published last year in AMA Journal of Ethics, centered on the case study of a 52-year-old woman with a hoarse voice and trouble swallowing who had a history of obesity and obstructive sleep apnea. She couldn’t lay flat without shortness of breath due to a large benign thyroid mass that deviated her trachea and narrowed its oral opening. The patient elected to undergo a total thyroidectomy.

Discussing an airway plan, the anesthesiologist recommended fiberoptic intubation — a more conservative, less risky approach to securing the airway that would keep the patient awake and breathing on her own while her breathing tube was placed and secured prior to general anesthesia induction. The surgeon, however, feared the patient would feel terrified and panic during fiberoptic intubation, and the junior anesthesiologist deferred to the surgeon’s plan to rapidly secure her airway via a rigid bronchoscope.

With the patient in a 45-degree head-up position, the anesthesiologist administered anesthetics and paralytics and placed an oral airway but had difficulty securing it. The provider implemented a two-handed technique to mask ventilate the patient, but oxygen saturation continued to fall. Direct laryngoscopy was then attempted, but the vocal cords could not be visualized.

After another failed attempt at mask ventilation, the surgeon attempted several times to place the airway via rigid bronchoscope, but the patient’s oxygen saturation, blood pressure and heart rate fell, indicating looming cardiac arrest. Finally, the airway was secured, the patient stabilized and the surgery proceeded. Both providers were relieved but shaken, and resolved to examine the event and see how they could better collaborate.

The authors say this example illustrates the need for better preoperative communication between surgeons and anesthesiologists. "All team members' concerns should be voiced, heard, considered and addressed well in advance of surgery on a patient to allow time for good decision making and inclusive discussion, confirmation of available equipment, and an organized approach to managing a patient's care," they write. "In particular, the patient’s airway management plan needs to be discussed by the surgeon and anesthesiologist and agreed upon before a patient is taken to the operating room."

The authors say the unique skill sets of the surgeon and the anesthesiologist should be respected. "The anesthesiologist’s communication of a pharmacological approach to sedation during an attempted awake fiberoptic intubation might alleviate the surgeon’s concerns about patient comfort," they say of the case study. "Alternatively, a surgeon’s adeptness and experience with an available rigid bronchoscope might mitigate an anesthesiologist's concerns that a patient remain spontaneously ventilating during the induction process." They add that the patient should also be aware of and sign off on the airway plan.

"Despite its high-stakes implications for patient safety, operating room communication remains under researched," the authors say. "Surgeon-anesthesiologist relationships might be the most central factor in determining how effectively operating room teams function. As the case highlights, the dynamics between these two physicians — who might share, yield or compete for leadership in operating room settings — can ultimately facilitate or impede success."

They say intraoperative and postoperative airway management decisions should be informed by relevant considerations of a patient’s anatomy, likelihood of success with any planned strategy, image review and contingency planning. They encourage surgeons and anesthesiologists to better understand and appreciate their successes, learn from their mistakes, optimize their interdisciplinary relationships, and foster collaboration and a sense of accountability and collective ownership of patients' safety and care.

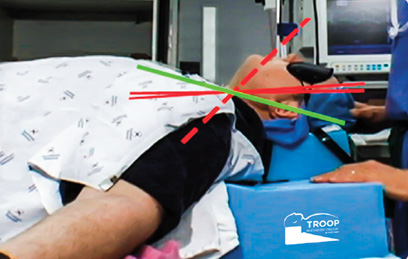

A BETTER VIEW Video laryngoscopes are invaluable tools for anesthesia providers as they navigate difficult airways.

A BETTER VIEW Video laryngoscopes are invaluable tools for anesthesia providers as they navigate difficult airways.

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)