- Home

- Article

Getting Better All the Time

By: Sonal S. Tuli, MD

Published: 7/3/2025

Treating keratoconus with surgical procedures and nonoperative methods has greatly improved over the years.

In the good old days, keratoconus was the most common reason people received corneal transplants. That was really the only option to treat the later stages of the progressive condition that begins in childhood.

Now, there are much better ways to improve patients’ vision before you get to a point where surgery would be an appropriate option. There are treatments that can stop, or at least attempt to stop, the condition from getting worse if a doctor detects that it’s progressing.

Because there are so many other treatments for keratoconus, the condition is now a very uncommon reason we do transplants. Transplants are still a good and relatively common option, but they’re not nearly as prevalent as they used to be.

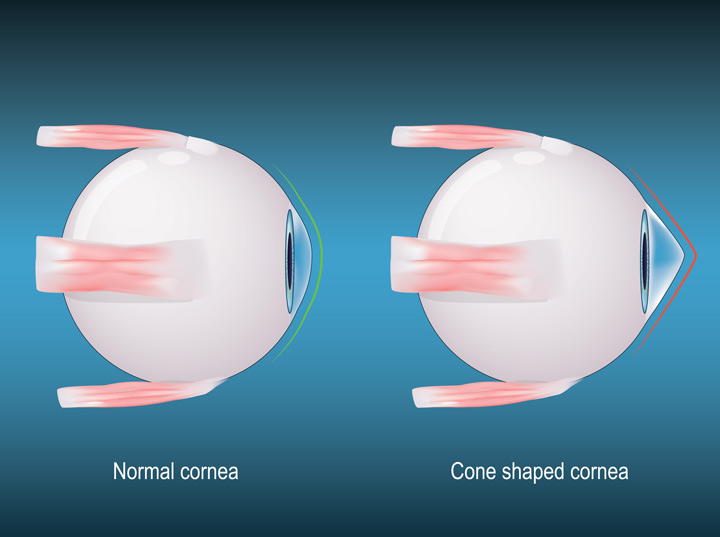

Keratoconus usually happens in kids and progresses until they’re in their 30s. The cornea, which is the clear front part of the eye, is curved and the shape of a baseball in most people. Sometimes it can be the shape of a football if it has a little astigmatism, which is fairly common, where one part of the cornea is more curved than the other. This can be corrected with glasses or contact lenses and when a cataract develops, it can be corrected with a toric intraocular lens (IOL) and other methods.

With keratoconus, patients also have an irregular cornea, but it’s not symmetric. This causes a bulging of the cornea, mostly inferior and sometimes inferior and outward. This makes the cornea pointy like the end of a football, instead of nicely curved. This is due to the thinning of the collagen tissue that makes up the cornea. Instead of being tough and holding its shape, it weakens and bulges.

Inherited conditions that are associated with keratoconus include Down syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, which affect collagen elsewhere in the body, as well as Leber congenital amaurosis. Rubbing the eyes extremely hard due to allergies or other irritants can also be a cause. People who have keratoconus tend to rub their eyes much more vigorously than other people. We educate patients not to do that, as it can make the condition progress.

Treatment options. Regular glasses don’t help very much after the very early stages of keratoconus. After the shape of the cornea becomes irregular, you can no longer make a pair of glasses to treat the astigmatism. Hard contact lenses that float on the tear film on the eye help at this stage. These hard lenses are spherical, like a baseball, so they cover the pointy cornea and correct the vision.

If the cornea gets pointy enough, however, even the hard lenses won’t fit because they teeter-totter on the eye and eventually fall off. That’s when the corneal transplant option becomes a consideration.

Contact lenses have gotten better and better over the years. We can now make large scleral contact lenses that go all the way out to the white part of the eye. These can treat much more significant keratoconus because they don’t teeter on the pointy cornea as the regular tiny contacts do. There are also piggyback techniques in which you put in a large soft lens first and then a hard one on top of it to make it fit better.

Impressions of the eye. There are technologies that can now create customized lenses for patients. It’s sort of like making dental implants with an impression of the patient’s teeth. With this technology, we can make a custom scleral lens and a prosthetic scleral cover shell, based on a custom impression of an individual eye. This too helps us better correct much more advanced keratoconus.

While this is usually done in an office setting, we often make these impressions for our pediatric patients in surgery centers, because the anesthesia makes it easier for the impression to be taken.

If the keratoconus continues to progress, it can go beyond the point where these custom lenses can treat it. As the cornea keeps stretching, its surface can scar and, if it stretches enough, the Descemet’s membrane in the back can tear. Such a tear pushes fluid into the cornea, which turns the cornea white and creates pain and sensitivity to light. (Those symptoms need to be treated with other procedures such as air injections or compression sutures.)

“Because there are so many other treatments for keratoconus, the condition is now a very uncommon reason we do transplants.”

Corneal cross-linking. This procedure is typically done in the office but is migrating to ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) to make it available to a wider population.

As kids with keratoconus are growing, their collagen is faulty, so it doesn’t harden when it should as their eyes stretch and grow, which is why the corneas become conical. With the cross-linking, we put riboflavin on the eye and then use a UV light to bond the collagen and make the cornea harder.

We’re moving many of these cases to the ASC because you often have kids who are young and would not be able to tolerate the procedure in an office setting. Often you need to remove all the epithelium, then the patient must sit there for 30 minutes getting eye drops and another 30 minutes getting the UV light. They must hold their eyes still the entire time, which they just can’t do, so anesthesia is necessary. There are reimbursement benefits to performing this procedure in an ASC instead of an office as well.

Cross-linking has revolutionized how we treat this condition. Now, if you notice rapid progression of keratoconus in a very young patient, you can slow it and, in some cases, stop it.

Early detection is the key. To slow or stop it, you must be able to catch it before it progresses to the point where surgical interventions become necessary, as there is already corneal scarring or very steep corneas present.

Transplants are tried and true. They work really well and they last a long time, because these are healthy eyes otherwise. You replace the cornea, but there’s also still the risk that the endothelial cells will gradually die out or the body could reject the transplants.

A lot of physicians have moved to the deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty, known as the DALK procedure. With the DALK, you leave the endothelium and the Descemet’s membrane behind while removing the rest of the cornea, the part in which the collagen is damaged, and you put in a transplant. This partial-transplant procedure reduces the risk of rejection and, if it rejects, it can be reversed without having a complete cornea failure.

DALK is performed in other parts of the world more than in the U.S. for a couple reasons. One is that it’s a comparatively difficult surgery to perform because you’re leaving the Descemet’s membrane behind. It is safer because the eye is not completely open, as it is when you do a full corneal transplant, but it takes longer to complete.

There’s also a learning curve. And, even though it takes longer, insurance pays less for a lamellar transplant than it does for a penetrating transplant, so physicians in the U.S. tend to do very few DALKs. Because they don’t do it a lot, they’re not very facile with it, which means they don’t have much success with it. It becomes a vicious cycle.

That’s why DALKs haven’t taken off in the U.S. They’ve sort of hovered around 1% to 2% of all transplants done, whereas if you look in the Middle East and other places, DALK is the primary treatment.

Another potential factor for the lack of growth is outcome-based. If you don’t completely bare it down to the Descemet’s membrane, the vision quality isn’t perfect. Whereas with the complete transplant, glasses or contacts, patients have excellent vision.

Intrastromal corneal ring segments. ICRSs involve a plastic ring that you can put into the cornea for keratoconus patients. You custom-make the rings to essentially push that coned cornea more centrally to make it more spherical so you can fit a contact or glasses over the eye. For some patients, the rigid plastic ring could cause inflammation or scarring and may cause melting and extrusion. That’s where corneal tissue addition keratoplasty (CTAK) or corneal allogenic intrastromal ring segments (CAIRS) came into the picture.

CTAKs on the rise. This procedure uses donated corneal tissue to make little corneal rings instead of using plastic. Sometimes, the donor tissue is from the smile lenticule from people who’ve had recent refractive surgery and, in some parts of the world, you can take a piece of donor corneal tissue from one person and use it on multiple patients. Physicians take out little partial rings from the donor cornea and slide them into small tunnels in the patient’s cornea to try to stabilize that cornea by moving the cone so it’s more central in order to correct the vision, similar to Intacs. CTAKs are still being optimized in various centers, but they’re available here.

Other options. People are making custom-made rings by mapping out the patient’s eye to see which parts are flat and steep. They make the ring in the same shape, which improves outcomes.

Other people have done what’s called a Bowman’s layer transplantation, in which they put a sheet of Bowman’s layer across the whole cornea. The Bowman’s layer is very dense corneal stroma. You can take a lenticule and then put it in the middle of the cornea or on the top of the cornea and let it heal.

These new methods are trying to supplement the thickness of the cornea. They require some specialized instrumentation, and the reimbursement codes are still being worked out because the procedures are new, but it’s slowly coming into place because it makes sense to do so. Patients with very thin corneas might do better if we thicken them up and make them less likely to expand.

Still in the lab. Putting more keratocytes in the cornea is on the horizon. This process grows living cells from stem cells that would be placed in the cornea to create more collagen and thicken up the cornea. Unlike most places in the world, there is no shortage of corneas in the U.S., but unfortunately that could change. Hospitals now rule out patients who have been admitted with sepsis as corneal donors, so there are worries that access could decrease.

There is research into biosynthetic or bioengineered corneas that would be the density you want and could be swapped out if needed.

And, of course, the holy grail would be some sort of gene therapy in which you could figure out which gene causes keratoconus and we fix it. OSM

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)