- Home

- Article

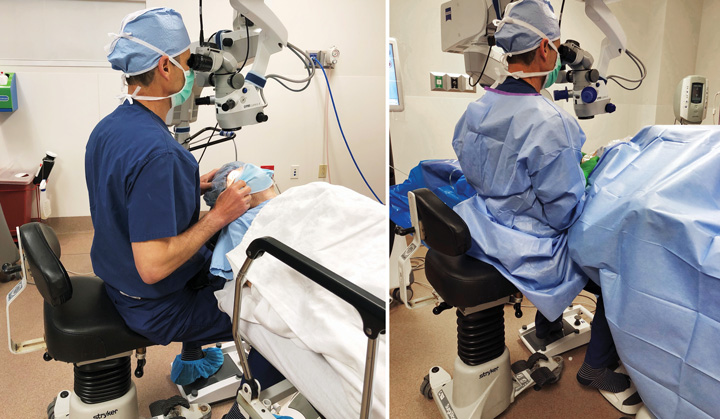

Improve Eye Surgery Ergonomics

By: Joe Paone | Senior Editor

Published: 4/6/2023

Your ophthalmologists could be suffering in silence with potentially career-threatening injuries.

You might be surprised by how many ophthalmologists suffer from occupational injuries that in some cases shorten their careers. After all, they’re not engaging in grueling orthopedic surgeries with power tools, standing over a surgical site for hours on end, or contorting themselves into awkward positions as they perform laparoscopic procedures.

The distressing fact is that two basic but tirelessly repetitive acts — sitting in a chair and peering into a microscope while performing delicate, precise procedures — can lead to severe neck and back injuries over time if an eye surgeon isn’t employing proper ergonomics.

Imperfect posture

Steven G. Safran, MD, PA, an ophthalmologist practicing in Lawrenceville, N.J., has lectured to peers at various meetings about ergonomics, and even modified the slit lamps he uses for eye exams to make them more ergonomically friendly — something he says numerous vendors have noticed and may replicate. “When you have very high-profile ophthalmologists who need neck surgery talking about the modifications they made to their equipment to survive, people get the message,” he says.

The topic hits close to home for Dr. Safran, who believes repetitive stress injury associated with poor ergonomics is an occupational hazard. In 2016, due to injuries the now-62-year-old physician had accumulated over many years in practice, he underwent a two-level fusion and had two discs replaced. “I had spinal stenosis, foraminal narrowing,” he says. “I was in a lot of pain and losing feeling in my hands. It brought to attention that you can’t just keep hammering away at your spine, because at some point it hammers back.”

His spine surgeon told him that he frequently operates on ophthalmologists and interventional radiologists. “I don’t know exactly the number of ophthalmologists who have injuries, but it’s very common,” says Dr. Safran. “A lot of my colleagues have had problems. This resonates with almost every ophthalmologist I know in their 50s and 60s — ‘Oh yeah, I’ve had injections, I’ve had fusion, I have back and neck pain, I see a chiropractor...’”

Dr. Safran expresses concern for younger, healthier ophthalmologists who may not take ergonomics seriously and could suffer injuries as they age as a result. “Young people don’t have a problem, they don’t have pain, they don’t feel bad,” he says. “By the time they realize there’s a problem, it’s too late because they’re already knee-deep in it.”

Dr. Safran was once one of those healthy young ophthalmologists. His spine surgery remains the only surgery he’s ever had. “I’d never been sick, never been injured, and then all of a sudden I was crippled,” he says. “I thought I might have to go on disability.”

Cumulative effect

Elizabeth Yeu, MD, an ophthalmologist with Virginia Eye Consultants in Norfolk, and president-elect of the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, estimates that more than half of ophthalmologists suffer from back and neck problems, and counts herself as one of them. “I have some underlying injuries to begin with that are just exacerbated by the strain of what we do day in and day out, how we are seated, the positioning, looking through the microscope and taking care of our patients,” she says.

“Part of it is because we are suspended,” she adds. “When we sit to operate, there’s nothing holding our core or our back, so we need to hold everything at the core and lean into the microscope.” Dr. Yeu says to keep everything steady, the best positioning is to keep the upper arms against the waist or ribcage, which supports the arms to provide the best stability and minimize any tremors. Even for the shortest cataract surgery, eye surgeons sit there in that position for a minimum of anywhere from six to 20 minutes, notes Dr. Yeu.

“I have seen surgeons who have had multiple surgeries at very young ages, surgeons in their 50s who are no longer even able to operate,” she says. “It’s so unfortunate, and it’s all related to ergonomics.”

Ergonomic tips

Both doctors agree that eye surgeons must essentially program their bodies and minds to avoid injury. It’s a challenging but achievable process, they say. Here are some tips they share with colleagues:

• Sitting. “Certain surgical chairs are friendlier to the provider, helping to support our gait and posture and central core better so we’re not just fully suspended,” says Dr. Yeu, citing one colleague who is developing such a chair as an example.

Dr. Safran, a firm believer in chair meditation posture, uses a saddle chair when performing surgeries. “I don’t worry about support behind me,” he says. “When I meditate, I don’t have my back against anything. I’m sitting straight up with my knees below my waist. I’m not slumped over, my back isn’t rounded. My ears are in line with my shoulders, my lower back is arched, my shoulders are back, and my arms are hanging a little lower. I’m not slouching forward so the weight of my head is out of line with my spine. I maintain this type of posture when I operate.”

• Breathing and positioning. “When we’re constantly looking through the microscope, our chin needs to be in the right position — not up, not down, but straight ahead — so we’re not putting repetitive strain on our discs that could lead to injuries,” says Dr. Yeu. “Our eyes should be positioned to look straight into the microscope, which is the ideal position. It’s important that our shoulders are not hiked up, that we are stretching.”

An ergonomically troublesome head-forward posture negatively impacts breathing, which leads to a cascading effect, notes Dr. Safran. “You tend to blow off carbon dioxide with shallow breathing, which leads to some respiratory alkalosis, which makes you more neuroexcitable,” he says. “That is not what you want when you’re trying to be very calm and have steady hands, so this actually translates into surgical performance.”

Both doctors agree that eye surgeons should focus on training themselves to breathe properly and to perform breathing exercises. “It’s a trained breathing,” says Dr. Yeu. “You breathe out of your nose twice as slowly as you breathe in. That stimulates the parasympathetic system, helps with pain control, and helps to calm anxiety. It is very helpful when I just need to slow things down due to an anxious patient or scenario. I just double my breathing-out time. The more I do that — and I’ve done it for five or six years now — the better I’ve become at it. I’m able to refocus more quickly and more intentionally as I need to.”

Dr. Safran points to traditional meditation techniques for cadenced breathing such as the 4-7-8 method. “Take a deep breath in for four seconds, hold it for seven seconds and breathe out for eight seconds,” he says. “It’s kind of hard to count those things off while you’re operating, though, so you need to program yourself to breathe deeper using your diaphragm.” Dr. Safran says if your posture is bad and you’re using your shoulders to breathe, you’re not using your lungs properly and you end up with a higher respiratory rate that causes you to blow off carbon dioxide and get respiratory alkalosis, which results in lowering your buffering capacity. “If you do this on a chronic basis, it becomes very easy to trip yourself into a situation where you get nervous and jittery, your veins become shakier, you get muscle spasms and you’re very neuromuscularly excitable,” he adds.

Breathing and meditation are very helpful with posture, says Dr. Safran. “Ancient disciplines like pilates, tai chi and yoga all have this in common,” he says. “It’s an important way to get your mind in the right place and in tune with what your body is trying to do.” The challenge, he says, is mindfulness, especially during a busy day packed with multiple surgeries and patient interactions. “When you’re focusing on your work, it’s not at the front of your frame of mind,” says Dr. Safran. “You need to program yourself to do the right things without necessarily being consciously aware of it all the time. It’s like learning to play a musical instrument. You can’t do it just by thinking about it.”

Dr. Yeu agrees. “We need to train ourselves because it’s so easy to lose good posture,” she says. Her assistants sometimes provide help in that regard. “My CRNA occasionally will let me know that my shoulders are up by my ears,” she says. “I like it when she reminds me to bring my shoulders back down, because when they are up it makes everything that much tighter, which then brings on the headaches and upper back and shoulder issues that make things much more challenging for me.”

• Exercise. Dr. Safran is dedicated to priming his body and mind for his work through exercises such as chin tucks, shoulder squeezes and back arches, which he does in addition to his other workouts. “I do the chin tucks and shoulder squeezes in the morning when I meditate, or sometimes when I’m driving home,” he says. “There are a bunch of exercises I do upside-down on an inversion table as well. I hang upside-down and stretch my back and spine, touch my toes upside-down with the kettlebell, do lots of upside-down sit-ups that stretch your spine. I do some rotational stretches too. If you know what you’re doing exercising, you can get a good workout with very basic equipment — a jump rope, a medicine ball.” Dr. Safran feels the combination of exercise, meditation and mindfulness training optimizes his body and mind for the rigors of his work.

Extending careers

In Dr. Safran’s view, the most important thing eye surgeons can do to prevent injuries is to be aware that they can develop and become proactive and conscientious about preventing them. “The point is, if you are using equipment that is forcing you into bad posture and bad positions, and you’re not aware of it, over time you’re very likely to have an occupational injury,” he says. Dr. Yeu takes a holistic view of the challenge. “We need to do everything we can do to help make certain that we’re extending our musculoskeletal lives so that our physiologic lives match our spiritual and intellectual lives,” she says. OSM

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)