Running a surgical facility during the pandemic requires wearing many hats while keeping several balls in the air and numerous plates spinning. Norma Bacon, administrator at the New England Surgery Center in Beverly, Mass., knows the drill all too well. She recently ticked items off her daily to-do list: check the facility's bank account, touch base with the staff, review the case schedule, tackle the mounting stack of papers on her desk, organize the facility's bills, meet with the physician owners, review payroll records and pause, deep breath...

"Well, you get the picture," laughs Ms. Bacon, who felt like she was close to treading water just before the pandemic hit. Instead, she's adrift in a sea of additional responsibilities, including keeping tabs on the facility's COVID-19 binder that contains current guidance from the CDC, Medicare and the state department of health — no easy task considering the directives change constantly. She wrote and rewrote the facility's pandemic response plan on the fly, and spent considerable time filling out numerous applications to secure stimulus money provided by the CARES Act. All the while, she's been going back and forth with the state and dealing with red tape to get approval for a new OR the center wants to build.

"I once tried to keep track of what I do on a daily basis," says Ms. Bacon, "and gave up because I didn't have enough time to do that."

Her experience isn't unlike the 452 surgical leaders who responded to Outpatient Surgery's annual salary survey. They took on more of a workload for similar or even reduced take-home pay, while dealing with the added stress of leading staffs during the pandemic's most difficult days.

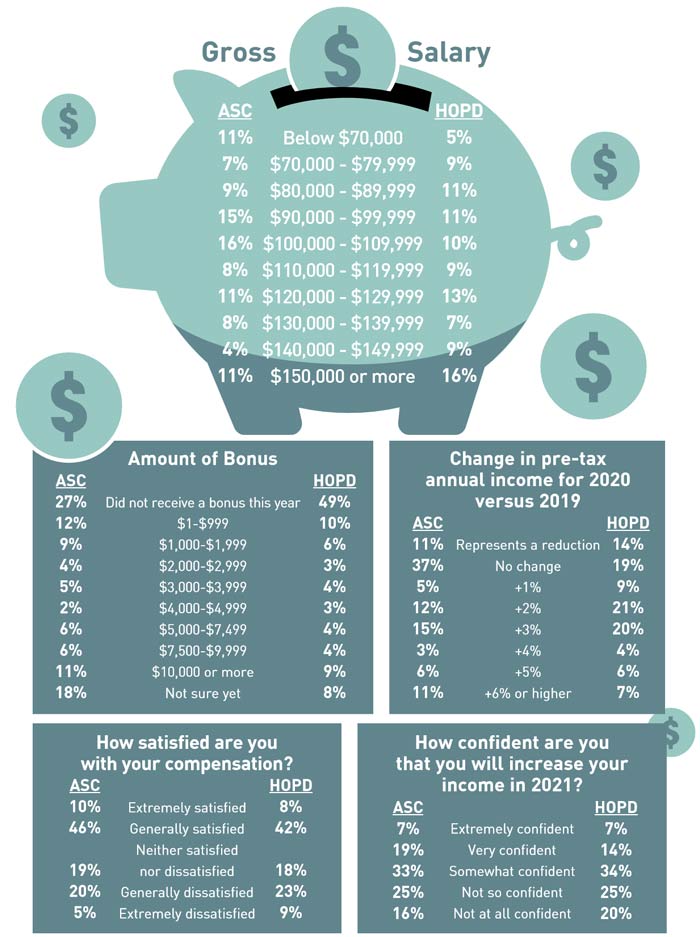

According to the survey, 11% of ASC respondents and 14% of HOPD respondents reported reduced income in 2020, while 37% of ASC respondents and 19% of HOPD respondents reported no change in income. All told, nearly half of ASC respondents and a third of HOPD respondents didn't sniff a pay raise. That's a sharp contrast from the 2019 survey, when only 28% of ASC respondents and 22% of HOPD respondents reported they hadn't received a raise, with just a tiny sliver of those receiving lighter paychecks.

Many of last year's reductions in pay can be attributed to the disruptive early stages of the pandemic, when elective surgeries were halted across the country and facilities scrambled to stay afloat. "During the months we were shut down, I was working from home and took a 25% pay cut," says Leah Reyes, RN, nurse administrator at Dallas Surgi Center.

Matthew Moore, BSN, RN, director of nursing at Comprehensive Spine & Pain in Villa Rica, Ga., also took a personal hit because of the elective surgery shutdown. "I'm an hourly employee," he says, "and it affected my pay by about $20,000."

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)