• Oral and IV analgesics. Acetaminophen, ibuprofen, celecoxib and gabapentin can all be used pre- and postoperatively instead of opioids. Some combination of these, possibly in addition to other measures, goes a long way

to reducing pain and post-op nausea and vomiting (PONV), constipation, urinary retention and sedation — all of which are bad for the patient’s experience and prevent safe and timely discharges. IV drugs such as ketorolac, ketamine,

magnesium and dexmedetomidine are part of many multimodal cocktails as well. Simply avoiding the effects of PONV, which can be so profound that some patients would rather deal with the surgical pain itself, makes using these drugs instead

of opioids worth it. Too much acetaminophen can be bad for the liver and too much ibuprofen can take its toll on kidneys, so it’s important to rotate their use, or use small amounts of each in concert with the other and not prescribe

more than the safe daily dose of each medication.

• Regional anesthesia. Nerve blocks — when anesthesia providers inject, with the help of ultrasound guidance, a local anesthetic near a nerve cluster close to the surgical site — are an important intervention

in many multimodal regimens. When patients receive an interscalene block during a painful shoulder surgery, for example, it not only helps intraoperatively, it also provides 24, 48 or 72 hours of relief downstream from the procedure, so fewer

pain medications will be required when they’re home. Reduction of postoperative pain might also allow patients to participate in physical therapy earlier and with less discomfort.

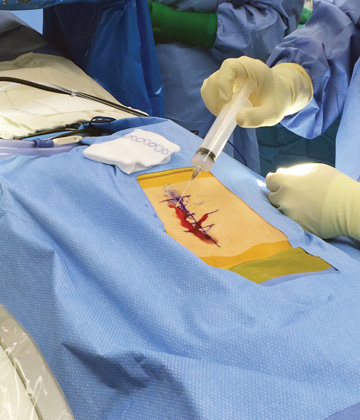

• Infiltration anesthesia. Single-shot injections of long-acting liposomal bupivacaine or ropivacaine administered at the surgical site near the end of surgery can provide days of post-op pain relief. The injections target

pain signals at the surgical site and can allow patients to avoid medications that can cause impairment, which can prevent early ambulation. The encapsulated anesthetic breaks up and is released over time, providing two or three days of extended

relief.

• Continuous nerve blocks. For some orthopedic procedures or other types of surgeries that are expected to cause a degree of pain that a single-shot anesthetic might not help, a catheter pain pump might be a better option.

Electronic pumps provide targeted pain control as the medicine flows from the pump into the incision via a catheter intermittently in preprogrammed boluses. In some instances, patients have the ability to release an extra dose when experiencing

breakthrough pain. Less techy elastomeric pumps steadily release the anesthetic and are disposed of when the bulb holding it is empty.

• Cryoanalgesia. While still used mostly for treating long-term chronic pain, cryoanalgesia is sometimes used as a bridge to give prospective surgical patients weeks or months of relief if they are still on the fence about

undergoing a joint replacement. Cryo is also beginning to be used to treat post-op surgical pain in some places. The practice consists of guiding a closed probe percutaneously next to the intended nerve bundle and using carbon dioxide or nitrous

oxide to essentially create an ice ball that freezes and disables the nerves. Some patients experience several months of reduced pain — or have none at all.

• Tailored approaches. While the point of ERAS protocols is to standardize practices so patients undergoing all kinds of procedures receive the treatments they need to reduce their stress response to having surgery, and the

objective of multimodal pain regimens is to reduce opioid consumption, every patient is different. So it’s important to tailor these practices to the patient. For example, older individuals often get very sleepy from gabapentin,

so an individual patient-centered approach to medication administration might be best practice.

When two or more drugs or interventions that don’t include systemic opioids are used, patients do better.

The prehabilitation of surgery patients — including educating them about their procedure, attempting to minimize their smoking, crafting a pre-op nutrition plan for them and of course managing their pain — all need to be tweaked based

on their overall health profiles. Tuning patients up, rather than just allowing their comorbidities to arrive for surgery with them, increases the quality of outcomes.

• Comprehensive education. Pain was once heavily touted to be the fifth vital sign and providers were encouraged to make addressing and alleviating it a priority. This, of course, produced some measure of overprescribing

opioids, which patients began to expect. It’s critical that their expectations are managed before surgery by explaining that they are going to be experiencing a certain amount of pain afterward.

This naturally leads into a conversation about how the non-opioid mix of treatment they’ll be receiving will work to eliminate most of their pain. Ask them to partner in their experience by following all discharge and physical therapy directions,

and set appropriate postoperative pain expectations in terms of the opioid alternative treatments and medications they’ll receive. Patients have come to not only understand this, but in many cases seek out providers who use little to

no opioids as part of the post-surgical experience because they’re aware of all the detrimental side effects and don’t want to experience them.

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)