The facility also uses a patient hand-off form, which contains the most pertinent patient information; it is only used between staff and not part of the official medical record. It communicates info such as most recent vital signs, allergies,

blood glucose level and fall risk assessment.

• Safety checks. In pre-op, the operative eye is marked only in conjunction with looking at the consent form. A skin marker is placed below the eyebrow to ensure it is visible during the time out in the OR, while a red or green

sticker placed above the eyebrow coordinates with the lid color of the eyedrops the patient receives. “A red top is for dilation and a green top is for constriction of the pupil,” says Ms. McCafferty. The nonoperative eye, meanwhile,

is covered with a clear plastic shield the patient wears until the surgery is completed. The shield prevents not only wrong-eye surgery — something that has never occurred at the center — but also intraoperative injury.

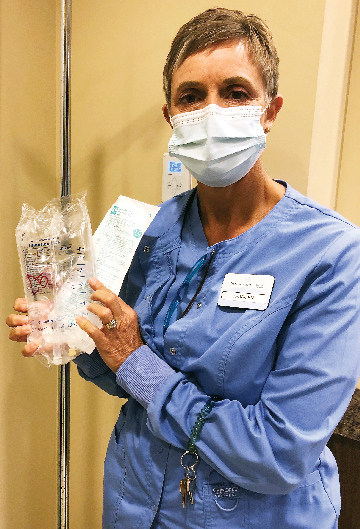

An identification band with the patient’s name and date of birth is placed on the patient’s ankle because their arms are tucked and covered before the procedure. Stickers are annotated with allergies so when the patient is taken to

the OR, techs know to set up appropriately if the patient has a latex allergy. “Name alerts” inform staff about patients that day with lookalike or soundalike names.

As the nurse enters the OR with the patient, an informal time out is performed during which the nurse and tech review the consent, the patient’s ID band, procedure, implant and allergies. In the surgical field, custom medication labels ensure

everything is labeled properly. Another formal time out is completed when the surgeon and anesthesia provider are both ready.

• Near misses. “We use a near-miss form to self-identify or report close mistakes that were almost made,” says Ms. McCafferty. “We track this to see if we have trends in certain areas.” The process is nonpunitive

and used for educational purposes. For example, staff notes if a wrong lens or implant is pulled — anything where they went through a process and something was not caught that could have been a big deal. “I go back and look at

where we are deficient,” says Ms. McCafferty. “We’ve caught and changed the way we do things through this self-reporting process.”

• Tracking post-op issues. Eye 35 ASC tracks infections every month, which given its sterling patient safety record would almost seem a formality if the center weren’t so thorough. “We give the surgeon a list of all their

patients going two months back, and they notate if they’ve had any post-op complications or infections,” says Ms. McCafferty. “We’ve not had a single infection since we opened.”

• Emergency preparedness. The center has a rapid response for evacuation and activation of its emergency plan. Red magnetic signs that say “CLEAR” are stationed inside each room’s door frame. In the event of a real

fire or a drill, the sign is moved to the outside door frame to indicate no one else is remaining in the room. The signs are in every room, including the restrooms and supply room.

A red box in the nurse’s office serves as Eye 35’s Emergency Preparedness Kit. Designed to be carried for use outside the facility, it contains a binder with all policies regarding possible disasters, staff emergency contacts and a

list of emergency numbers other than 911 for electric, plumbing, HVAC and more. In case of emergency, role cards with duties for each staff member can be distributed. The box also contains a handheld radio and charging cords for radios and

computers.

Staff with ideas to make patients safer are encouraged to suggest ideas whenever they have them. “It’s not a formal process,” says Assistant Clinical Director Karen Dargan, BSN, RN, CNOR. “We work closely with everyone,

so it usually comes up in casual conversation.”

Once an idea is investigated and approved, it is immediately imparted to everyone who needs to know. “We send an email to the staff about it, and if it requires training, we conduct lunch-and-learns,” says Ms. McCafferty. “If

it’s department-specific, we huddle in the morning. Not everybody handles change the same, so we always tell them, ‘This is why we’re doing it.’”

The tight-knit center, home to about 24 clinical and office staff, is never finished when it comes to patient safety — a testimony to its aggressive commitment to process improvement and efficiency. “We’re trying to work smarter,

not harder,” says Ms. McCafferty. “That’s our motto around here.” OSM

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)