- Home

- Special Editions

- Article

Do Cold ORs Cause SSIs?

By: Kendal Kloiber | OSM Contributor

Published: 5/1/2025

Experts say maintaining patient normothermia is more complex than just adjusting the thermostat.

Operating room temperatures have long been a point of contention among clinical staff and surgical teams. Scrubbed personnel often prefer cooler environments to stay comfortable under layers of protective clothing, while others believe warmer ORs are necessary to prevent surgical site infections (SSIs).

So, does a cold OR really increase the risk of SSIs?

Beyond the thermostat

The relationship between cold ORs and SSIs is nuanced rather than a simple case of cause and effect, according to Harriet Hopf, MD, professor and executive director of faculty development and academic affairs in the department of anesthesiology at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

“A cold OR in the absence of other steps to maintain normothermia can contribute to a patient becoming hypothermic,” she says. “But in the modern OR, we have tools to keep patients warm without overheating staff or equipment.”

David Etzioni, MD, a colorectal surgeon and researcher with the Mayo Clinic and chair of the surgical and procedural committee of Mayo Clinic Enterprise in Arizona, agrees the issue is complex and conducted research to prove it.

“It’s very hard to simplify down to one straightforward statement,” he says. “Our study of 15,000 patients showed no clear relationship between OR temperature or humidity and the risk of surgical site infections.”

Hypothermia is the real culprit

The real issue, then, isn’t the ambient temperature of the OR. It’s the patient’s core temperature.

Hypothermia, defined as a core body temperature below 96.8°F (36°C), has been shown to increase the risk of SSIs and other postoperative complications, says Dr. Hopf. Under general anesthesia, patients lose their ability to regulate temperature through autonomous behaviors (like adding layers) and physiological mechanisms (like vasoconstriction and shivering).

Anesthetic drugs impair the body’s thermal regulation. They dilate peripheral blood vessels, increase heat loss and widen the hypothalamus’ temperature threshold. All of that blunts the body’s natural response to cold.

“Your body just doesn’t care as much about getting cold under anesthesia,” says Dr. Hopf. “You lose core heat rapidly — as much as one to one-and-a-half degrees in the first 30 minutes.”

That temperature drop can lead to cascading effects. Wound healing requires oxygen to power immune cells, support new blood vessel growth and build collagen. Hypothermia reduces blood flow to the skin, limiting oxygen delivery when it’s needed most. Cold neutrophils and platelets are also less effective, weakening the body’s defenses against infection and impairing clotting.

“All cells are temperature-dependent,” says Dr. Hopf. “A cold white cell or platelet isn’t as efficient at killing bacteria or stopping bleeding, which in turn can slow healing and increase infection risk.”

Dr. Etzioni says hypothermia can affect drug distribution and heart rhythm stability. “Hypothermia can also impair coagulation, increasing the risk of bleeding and the need for transfusion,” he adds.

Patient variables

While all surgical patients are susceptible to hypothermia under anesthesia, some populations are at greater risk and warrant closer monitoring. Underweight patients, for example, tend to lose body heat more rapidly due to a lower insulating fat layer and smaller body mass. These individuals are particularly vulnerable during long procedures or in cold environments.

Conversely, obese patients may be at risk of overheating, especially if they’re fully covered during surgery, notes Dr. Hopf. That makes temperature management a balancing act of maintaining normothermia without causing hyperthermia.

Pediatric and geriatric patients also face heightened risks. Children have a higher body surface area relative to their weight, which leads to more rapid heat loss. Older adults often have a diminished physiological response to cold, including reduced vasoconstriction and shivering, which makes it more difficult for them to maintain core temperature, says Dr. Hopf.

Patients undergoing large, open surgeries such as major abdominal procedures are another high-risk group, says Dr. Etzioni. These cases often involve significant exposure to ambient air and fluids, which accelerates heat loss. Preoperative warming, intraoperative active warming and diligent postoperative temperature monitoring are particularly important in these scenarios to minimize complications and support recovery.

“The types of surgery that result more often in hypothermia are ones that expose a large surface area of the body to the air,” he says. “In our operations, the shift from open procedures to minimally invasive surgery has helped us to reduce the impact of the OR’s temperature on heat loss.”

While OR ventilation systems are important for overall air quality and infection control, their role in preventing SSIs is less definitive than commonly assumed.

Laminar airflow systems, designed to reduce airborne contamination by directing clean air across the surgical field, are widely used, especially in orthopedic and implant surgeries.

“Research hasn’t shown them to significantly reduce SSIs, and in some cases, they may even harbor bacteria if not properly maintained,” says David Etzioni, MD, a colorectal surgeon with the Mayo Clinic.

He notes that bacterial contamination can originate from multiple sources — patient skin, internal organs or the surgical team itself.

“That’s why we wear masks and, in some specialties, full spacesuits to keep exhaled bacteria away from the wound,” he adds.

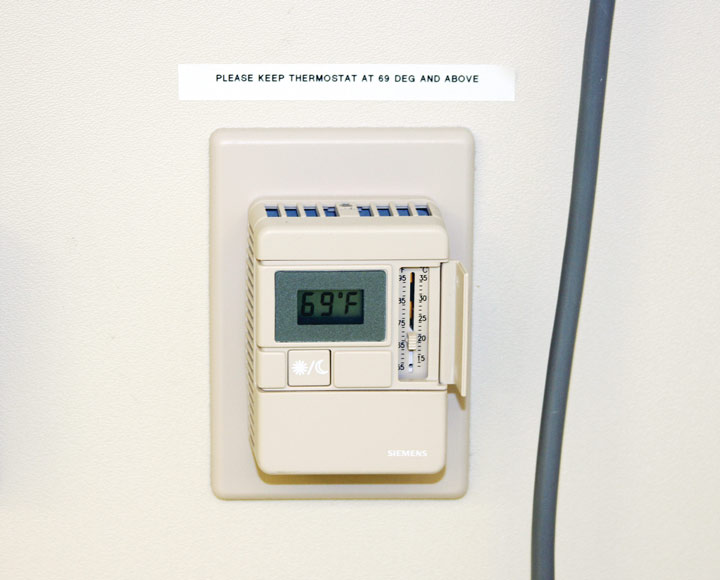

The Joint Commission adheres to American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) standards that recommend OR temperatures between 68°F and 75°F and humidity levels between 20% and 60%. While these ranges help support safe operating environments, facilities are permitted to operate outside them on a case-by-case basis with surgical team approval, notes Dr. Etzioni.

— Kendal Kloiber

Keeping patients warm

Warm blankets may be a patient favorite, but they’re more comfort than cure. “They feel nice, but they don’t actually transfer heat back into the body,” says Dr. Hopf. “They just slow further heat loss.”

Active warming devices such as forced-air warming systems are Dr. Hopf’s preferred method. These systems circulate heated air through a specialized quilt or gown, effectively transferring warmth to the patient. A 1996 randomized clinical trial showed that forced-air warming during colon surgery reduced SSIs by two-thirds.

Preoperative warming is especially effective. Warming patients before they enter the OR helps create a thermal reserve, reducing the impact of anesthetic-induced vasodilation and heat redistribution, says Dr. Hopf. It’s also a valuable tactic in ASCs, where patients are often awake and appreciate the added comfort.

“If you can take that skin-level temperature and raise it before anesthesia, then the core temperature drop is less dramatic when anesthesia is induced,” explains Dr. Etzioni.

Dr. Hopf says implementation of pre-op warming can take some effort, but emphasizes that it’s worth it. “When patients arrive in the OR already warm and vasodilated, their temperature drop is smaller and recovery is smoother,” she says. “Even starting warming as soon as they enter the OR can make a difference.”

Other active warming strategies include circulating fluid blankets, warmed IV fluids and the use of warming gases in anesthesia circuits.

“The intensity of warming should be tailored to the patient’s risk,” says Dr. Etzioni. “Pediatric patients, very thin elderly patients and those undergoing long or fluid-heavy surgeries need extra care.”

At Dr. Etzioni’s institution, this means applying prewarming protocols to patients undergoing major abdominal surgery, particularly for those at risk for significant heat loss. He notes that the key to success is consistency and integration into the clinical workflow.

“We try to incorporate warming into our standard prep process, especially for high-risk cases,” he says. “It doesn’t need to be elaborate — just reliable. The earlier you intervene, the more likely you are to preserve normothermia and avoid downstream complications.”

A case-specific decision

Whether to keep the OR warm or cool should be a decision based on patient population, procedure type and workflow. For short, low-risk outpatient procedures, prewarming and patient comfort may be the priority. For longer, invasive surgeries with higher infection risks, maintaining normothermia throughout the perioperative period is crucial.

The experts emphasize that staff comfort matters, too — especially for the scrubbed team.

“Scrubbed personnel can’t strip off layers,” says Dr. Hopf. “Keeping them cool helps them stay focused and avoid contaminating the field through sweat.”

Dr. Etzioni agrees, adding that surgery is a team sport that depends on thoughtful coordination.

“Planning and collaboration are key,” he says. “You want to maintain an OR environment where the patient is warm, but the surgical team can still perform at their best. If the surgeon is overheating or distracted, that can impact outcomes just as much. We need to consider all aspects of the OR experience — not just the thermostat setting.” OSM

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)