Regional anesthesia still might be generally underutilized, but Dr. Mariano says blocks are beginning to be used more frequently thanks in part to numerous improvements in block techniques. For example, there’s been a steady uptick in

the use of interscalene brachial plexus blocks during shoulder replacements, distal peripheral blocks for upper limb surgeries, and popliteal sciatic blocks for foot and ankle procedures and arthroscopic surgeries for the treatment of

sports injuries.

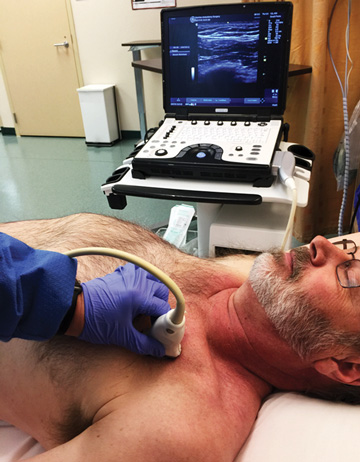

These developing blocks are placed more easily and accurately thanks to ultrasound machines with larger screens, clearer images and user-friendly controls. “The clarity and sharpness of the image as well as the imaging processing power

create a more defined image, which makes the procedure easier,” says Mike MacKinnon, DNP, FNP-C, CRNA, an anesthesia provider at Northeastern Anesthesia in Show Low, Ariz. “Looking for differences in nerve patterns on old snowy

screens compared with now actually seeing the fascicles of the nerves is a tremendous advantage.”

He adds that larger screens and intuitive controls found on newer ultrasound units help with efficiency and ease of use, but other functions such as automated image enhancement technology allow providers to visualize needles “in-plane,”

even when inserting them at a steep angle. “That would otherwise be much harder to do,” says Dr. MacKinnon. “These upgrades have made it easier to visualize the needle, danger zones and target nerves, making placing a

block with ultrasound guidance safer, more effective and easier.”

Innovations in ultrasound guidance are also leading to the continued development of emerging blocks that are likely to play a larger role in the future of patient care. Many of them are allowing more patients to undergo surgeries at outpatient

facilities. For example, placing the pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block in total hip patients is a technique Dr. MacKinnon frequently uses. “This block involves depositing local anesthetics in the fascial plane between the psoas

muscle and the upper pubic branch, effectively targeting the anterior hip capsule by blocking the articular branches of the femoral nerve and accessory obturator nerve,” he says. The PENG block is a better option than the femoral

nerve block or lumbar plexus block because it avoids quadriceps weakness and allows patients to ambulate much more quickly, according to Dr. MacKinnon.

Dr. Mariano expects to see more “personalization” of regional anesthesia moving forward. “We know there are certain surgeries that hurt more, but we also know each individual patient might experience pain from the same surgery

in a different way,” he says. “We’re only just scratching the surface of understanding how many inter-individual differences there are.”

Although providers don’t yet have the information they need to make accurate predictions about which blocks would work best on individual patients, Dr. Mariano thinks providers will be better able to predict trajectories of pain based

on patients’ genotypic differences as more outcomes data is collected. “Once we can account for those differences, we’ll be able to better understand, for example, which patients would benefit the most from shorter or

longer blocks,” he says. “Some patients might also need higher- or lower-intensity blocks. I think that will help to contribute to a more personalized approach to pain management.”

.svg?sfvrsn=be606e78_3)

.svg?sfvrsn=56b2f850_5)